The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (“TCJA”) signed into law on December 22, 2017 changed the alimony landscape significantly. Before TCJA, alimony payments were deductible by the payor and taxable to the recipient. After TCJA, for divorces finalized on or after January 1, 2019, alimony is not deductible and not taxable income to the recipient.

So, who is affected more? The alimony payor or the recipient? The impact of this change is not immediately obvious, especially on how eliminating the deduction can influence the determination of alimony.

Taxes Affect the Need for and Ability to Pay Alimony

In Florida, alimony entitlement is derived from the ability of one spouse to pay and the need of the other spouse. The average US taxpayer spends approximately 22% of their household income on taxes. This makes tax a critical piece in determining someone’s ability to pay alimony.

The Old Days…

Before TCJA, the ability to pay alimony – essentially excess cash flow – was derived using a circular calculation of net cash after the alimony payment deduction. This was essential because the alimony payment provided a significant tax reduction or savings, especially for taxpayers in the higher tax bracket, which today is 37% but historically has been as high as 39.6%.

With alimony no longer tax deductible after TCJA, the payor’s excess cash flow is a straightforward calculation. That means no “after tax” cash flow calculation is necessary.

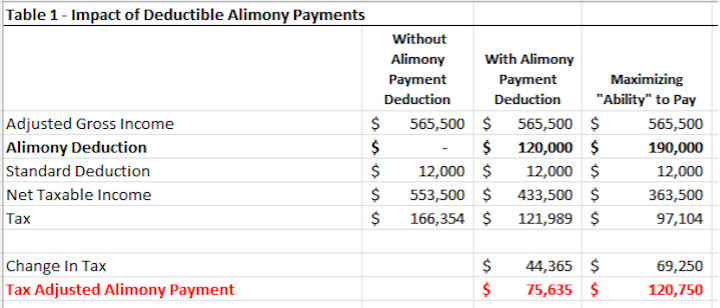

So, whom does this change most affect? See Table 1. When alimony was deductible, tax savings meant someone paying $120,000 of alimony was out-of-pocket only $75,635. If one were trying to determine the payor’s ability to pay $120,000 net (after taxes), the actual “grossed-up” alimony payment to the recipient would be higher, due to tax savings available to the payor from the deduction.

When alimony was deductible, for a payor’s net “out of pocket” payment to be $120,000, the gross payment to the recipient would have been closer to $190,000.

So why does this matter? On the surface there is no apparent difference because, prior to TCJA, the alimony payment would have also been taxable to the recipient. But many times, the recipient of alimony has few or no other sources of income. That means they are likely to be in a lower tax bracket than the payor. In other words, the recipient would not pay the same $44,000 or $69,000 tax that the payor would have saved by deducting alimony (See Table 1 for “Change in Tax”).

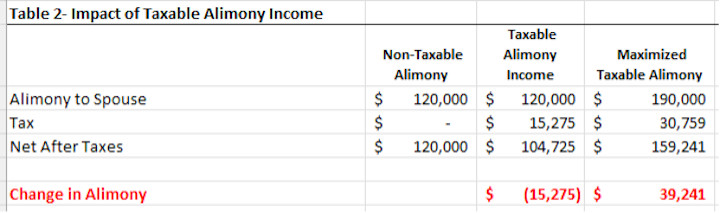

Let’s look at Table 2 for the tax impact on the recipient. A recipient reporting $120,000 of alimony income would have paid $15,275 in tax – almost $30,000 less tax than the payor saved on this deduction ($44,365 in Table 1). Likewise, in the case of a $190,000 alimony payment, the recipient would have paid a total tax $30,759 (Table 2). The result is, in the case of “maximized” alimony income, the recipient could have received almost $40,000 more in alimony after-tax than under the changed law, where the payor gets no alimony tax deduction.

The Alimony Pill: More Bitter than it Needs to Be?

Eliminating the alimony tax deduction has made alimony more of a bitter pill for many. Before, for many payors, deducting alimony made paying it somewhat easier to swallow. Indeed, many couples considering a divorce after the TCJA was signed into law in 2017 tried to rush to finalize their divorce before the new law went into effect in 2019.

Now that we can’t turn the clock back, what options are there? In the collaborative process, your neutral collaborative financial professional may explore these options with you and your collaborative team.

A Spoonful of Honey? Alimony Trusts

One creative way to make paying alimony less painful to the payor and more attractive to the recipient is to consider establishing a trust called an “alimony trust.” An alimony trust allows an alimony payor to contribute assets to a trust for the benefit of an ex-spouse. Although the contribution of assets to the trust will NOT represent a deductible alimony payment, attributes of the trust may make paying alimony an easier pill to swallow.

The person creating the trust would earmark assets that would generate income taxable to the ex-spouse receiving distributions from the trust as beneficiary. Simple income tax rules would apply to such distributions.

If, instead, the ex-spouse did NOT transfer those assets into an alimony trust, income the assets generated would be taxable to the ex-spouse (the alimony payor), who would turn around and make their alimony payments. By shifting those assets to a trust for the benefit of the ex-spouse, the taxable income on the alimony trust assets would be taxable to the recipient/beneficiary – thereby shifts income to the recipient/beneficiary.

But… when current law says alimony is not taxable, why would a potential alimony recipient agree to such an arrangement?

Making Things Sweeter: Benefits to Ex-Spouse as Beneficiary of Alimony Trust

There are several benefits to the ex-spouse receiving the trust payouts in lieu of traditional alimony payments:

- To meet lifestyle needs, the receiving spouse now has a guaranteed pool of assets available that doesn’t depend on the payor’s future earnings or financial condition.

- There is no risk the payor’s premature death could jeopardize cash flow from the trust to meet the recipient’s cash needs.

- There is no risk, if the ex-spouse receiving trust distributions remarries, the distributions would end.

- These trusts are typically established for the life of the ex-spouse (primary beneficiary), with the remainder earmarked for the couple’s children.

Exploring Options in the Collaborative Process

Divorce is a challenging process which could be made easier by working in a Collaborative setting to build options unique to each family’s needs considering their financial and tax circumstances. As the alimony issue illustrates, financial obligations don’t have to be bitter pills. Your Collaborative team may explore options to meet your financial goals and help the “medicine go down.”