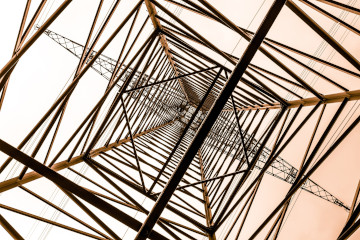

A Collaborative Professional’s ethics are as integral to a strong, successful Collaborative Process as a skyscraper’s steel skeleton is to its support. Where do Collaborative Professionals get their steel beams, rivets, and girders? Are ethical standards for Collaborative Professionals merely aspirational or are they foundational?

Collaborative Law is based on the Uniform Collaborative Law Act and Rule (UCLA/R). As of April 2023, by legislative enactments or court rules, 22 States and the District of Columbia have adopted it.

Florida did so in 2016. Florida’s legislature enacted The Collaborative Law Process Act, Section III of Chapter 61 (§61.55-§61.58, Florida Statutes) (the Act). The Act went into effect in 2017 when the Florida Supreme Court issued Florida Family Law Rule of Procedure 12.745, The Collaborative Law Process and Rule 4-1.19, Collaborative Law Process in Family Law, Rules Regulating the Florida Bar (RRTFB).

The Rules Regulating the Florida Bar require attorneys to explain the different options a client has in resolving their divorce disputes. Under Rule 4-1.19, a lawyer must explain the Collaborative Law Process to a potential client in describing Collaborative law as an option, to ensure a client choosing the Collaborative Process does so with informed consent.

Nearly 20 years ago, the International Academy of Collaborative Professionals (IACP) established Standards and Ethics to guide Collaborative professionals’ behavior in the Collaborative Law Process, regardless of where in the world the professionals are collaboratively practicing. See International Academy of Collaborative Professionals, Minimum Ethical Standards for Collaborative Professionals, initially adopted in 2004, revised in 2008 and restated in June 2017, available at: https://www.collaborativepractice.com/sites/default/files/IACP%20Standards%20and%20Ethics%202018.pdf

The Florida Academy of Collaborative Professionals (FACP) adopted its Standards and Ethics in 2018. They are almost identical to the IACP’s version. This blog will cite the IACP Standards and Ethics.

Different jurisdictions’ ethical rules are enforceable against Collaborative professionals practicing in the jurisdiction. For example, in Florida, Collaborative attorneys must abide by Rule 4-1.19 and the other Florida Rules of Professional Conduct. Florida Collaborative Mental Health Professionals (MHPs) must abide by ethical rules their licensing board has established (e.g., for psychologists, the Florida Board of Psychology; for Florida licensed mental health counselors, licensed marriage and family therapists, and licensed clinical social workers, the Florida Board of Clinical Social Work, Marriage & Family Therapy and Mental Health Counseling).

The IACP’s Standards and Ethics have not been adopted as official ethics of any jurisdiction. Therefore, although a Collaborative professional group such as the IACP or FACP may condition membership (or, for Accredited Collaborative Professionals, accreditation) in good standing, on adherence to the Standards and Ethics, they are not separately enforceable against the Collaborative Professionals licensing authorities.

Collaborative Standards and Ethics: Aspirational or Foundational?

Does the fact FACP’s Standards and Ethics have not been submitted for approval to the Florida Supreme Court make them any less compelling for the Collaborative Law Process (CP) to work? Should we Collaborative Professionals treat them as merely aspirational?

For the Collaborative Law Process to work, I suggest we need to treat the Standards and Ethics as foundational: the steel skeleton of the Process. Even when the Standards and Ethics may conflict with Rules of Evidence, with Rules of Professional Conduct, and sometimes even with the UCLA/R itself, Collaborative professionals should resolve these conflicts by applying more rigorous Standards and Ethics.

Three areas where the ethical framework for the Collaborative Process and rules governing professional conduct in the adversarial processes may conflict are: 1) confidentiality; 2) advocacy; and 3) use of the law.

CONFIDENTIALITY

Assume the clients and their lawyers have signed a Collaborative Participation Agreement. The Collaborative Process has begun. Separate from a team meeting, your client confides in you about an affair of which the other spouse is unaware.

Under normal circumstances, including attorney-client privilege under the Florida Rules of Evidence and RRTFB, and even the UCLA/R’s provisions on confidentiality of communications between lawyers and clients, this information could not be conveyed to anyone without the client’s consent. Such disclosure by the attorney would violate the attorney-client privilege, breach the attorney’s confidential relationship with the client, and violate Rule 4-1.6 Confidentiality of Information, RRTFB. Outside the Collaborative Process, the odds the client would grant permission for the attorney to disclose the information would be slim.

And, for that matter, Rule 1.2 Competence, IACP Standards and Ethics provides:

“A. Collaborative Professionals must comply with professional conduct requirements applicable to their professions.”

Still, one could argue the Participation Agreement and Florida’s Collaborative Ethical Rule, Rule 4.1.19(b)(4), RRTFB, require information such as your client’s confidences about the affair be disclosed in the Collaborative Process. Yet other people, including your client, could argue – vehemently – that such information is not related to the collaborative matter.

DUTY OF CANDOR IN COLLABORATIVE

Rule 3.1 A. of the Standards and Ethics provides:

The Collaborative Process requires the full and affirmative disclosure of all Material information whether or not requested.

The Standards and Ethics say you, as the attorney, are ethically bound to disclose “Material” information to the team, defined as information “reasonably required for the client(s) to make an informed decision with respect to the Resolution of the matter.” Standards and Ethics, 1.0.D. For this discussion, assume you conclude information about the affair is “Material” information.

So…what to do? Assume your client refuses to permit the disclosure of this information to the team or any of its members. What options do you have under these circumstances and why?

You may urge your client to let you disclose the information. Rule 3.8, Circumstances that Require Counseling Clients, provides for explaining to the client that the lawyer must resign as counsel if the client insists that the information may not be disclosed. If the client continues to insist that the information remain confidential under the attorney-client privilege, the attorney must resign under Rule 3.10.A. Resignation and Discharge.

Resignation is extreme. But its the only way to ensure the integrity and strength of the Collaborative Process – a voluntary, open, and transparent process resulting in final agreements clients must sign after informed consent. That is true not only for the immediate Collaborative matter before you, but also for the long-term integrity, health, and trustworthiness of the Collaborative Process.

Voluntary disclosure in the Collaborative Process is unlike “no-fault” divorce litigation, where information about an affair ordinarily isn’t disclosed, except under compulsion, over objection to relevance, or to avoid perjury, if your client is questioned about it directly.

Before your client selects the Collaborative Law Process, you must explain your ethical obligations regarding disclosing all “Material” information, whether or not protected under attorney-client privilege. If the client is unwilling to sign a Participation Agreement that includes the specific disclosure provisions of the IACP Standards and Ethics, the client likely is not a candidate for the Collaborative Process.

The Participation Agreement, which is a legally enforceable contract, will govern Rule 3.1’s interpretation and operation. Be precise in the Participation Agreement about disclosure. Pay attention to, understand, and explain to your client the phrases, “Material information” and “whether or not requested.”

If the Participation Agreement the clients will consider and sign is crafted with proper language, consent to disclose affirmatively Material information should already be included. In the Participation Agreement, state the consequences for a client’s later refusal to permit such disclosure.

There is so much more to be written about Rule 3.1, but not enough space here. For excellent expanded discussion about disclosure obligations in the Collaborative Process, see David A. Hoffman and Andrew Schepard, To Disclose or Not to Disclose? That Is the Question in Collaborative Law, FAMILY COURT REVIEW, Vol. 58 No.1 January 2020 83-108. Hoffman and Schepard recommend Collaborative Law practitioners incorporate the duty of candor that makes the Collaborative Process strong, effective, and special into standard Participation Agreements. Id. at 84.

ADVOCACY

Another conflict between ethics framing and supporting the Collaborative Process and ethics in adversarial processes is advocacy. The preamble to Chapter 4 of the Florida Rules of Professional Conduct: A Lawyer’s Responsibilities, says: “As an advocate, a lawyer zealously asserts the client’s position under the rules of the adversary system.” Under Rule 4.1.3 RRTFB, Diligence, “A lawyer must also act with commitment and dedication to the interests of the client and with zeal in advocacy upon the client’s behalf.” In an adversary system, ethics require lawyers to advocate, with zeal, positions on the client’s behalf.

In contrast, ethics framing the Collaborative Law Process—a nonadversarial, non-positional system—require lawyers to direct a different zealous focus and corresponding behavior towards resolutions that serve all client participants.

According to Rule 3.4.C. Professional Teamwork, IACP Standards and Ethics, “Each Collaborative professional must act in a manner that advances the interest of all clients in reaching resolution.” Does this mean the attorney doesn’t advocate zealously for the client in the Collaborative Law Process? The answer is no.

Rule 3.2, Advocacy in the Collaborative Process, Standards and Ethics, says a Collaborative Professional does advocate, but in a different way than a lawyer would in an adversarial process. In CP, a Collaborative Professional advocates by respecting each client’s self-determination, assisting the clients in establishing realistic expectations, encouraging clients to consider how their decisions may affect dependents, considering how the professional’s experience, values, opinions, beliefs, and behavior may affect the Collaborative matter, and avoiding contributing to the clients’ conflict, including when identifying and discussing the clients’ interests, issues, and concerns.

In litigation, you advocate for the client positions to get to the best deal. If it cannot be achieved, you have the option to try the case and the clients do not get to decide the outcome. The threat of court hangs over the heads of both clients.

But in the Collaborative Process, the disqualification provision means there is no fallback in your bailing out and no motivation for you to threaten to have the judge decide the case at trial. Instead, the collaborative matter is resolved by the clients’ self-determination with guidance from both attorneys.

Lawyers shifting their zealous focus from position-taking in litigation to advocating in the Collaborative Law Process for clients’ interests and goals must make a so-called “paradigm shift.” No threats, no coercion, no heavy handedness to “win” for the client. Lawyers move from positional advocacy to building options that benefit both clients.

Winning in Collaborative is when the matter is resolved for both sides and the family. Winning is when the clients can co-parent their children after the Process is resolved. Winning is when obtaining a divorce hasn’t destroyed the family. Winning is not where “one side” feels they’ve won and “the other side” feels they’ve lost. As family lawyers, do we wish to win at all costs for our client or to win by making sure neither party feels as if they have come away as a loser?

THE LAW

The Preamble to Chapter 4. Florida Rules of Professional Conduct: A Lawyer’s Responsibilities acknowledges a lawyer may act in different capacities: advisor, advocate, negotiator, and evaluator. In the Collaborative Law Process, a lawyer acts in all four capacities.

As an advisor, a lawyer provides a client with an informed understanding of the client’s legal rights and obligations and explains the practical implications. In rendering advice, a lawyer may refer not only to the law but also to other considerations, such as moral, economic, social, and political factors that may relate to the client’s situation. Rule 4-2.1 RRTFB. So, there is an ethical duty to communicate with the client about the law and what it provides. Without doing so, the informed consent the client must have to finalize the Process by signing a final agreement would be lacking.

How lawyers use the law in litigation differs from how they use law in the Collaborative Process. In the Collaborative Process, interest-based negotiations lead to a final resolution best achieving the collaborating clients’ interests. But in the adversarial process in family matters, each side argues the law and why a disinterested third party – the judge, magistrate or other person empowered to make final decisions – should apply it to evidence presented, to justify the claims or demanded relief of each side.

When, how, and where the law is communicated with the client is different in the two processes. When I was a trial attorney, I would immediately analyze how the facts fit in with the law to determine if this was a strong case for the client based on the law and would then discuss the good, the bad, and the ugly in relation to applying the law in the client’s case.

Then I became a Collaborative Professional. Since then, in my initial consultations, I educate clients on the different processes available. With informed consent, they may then choose the process that fits them best. I avoid discussing the law when I gather basic facts, because I don’t want clients to become positional and rigid in negotiations, which is counterproductive. Once clients believe the law is “on their side” on an issue, they may fail to consider different options, including options that could result in a superior resolution for them, their spouse, and their family.

The Collaborative Law Process provides option-building negotiation. Clients’ interests, so long as they are realistic, are used in arriving at a final resolution. Rule 3.3 Good Faith Negotiation, IACP Standards and Ethics, spells out how the clients engage in their negotiations toward a final resolution. As the Process goes forward, the clients must be made aware of what the law provides. It may be in full team meetings, privately with the clients, or with one or more of the other professionals present when discussing a particular topic.

Flexibility in understanding the timing and method of communicating the law is important. You don’t want the clients to become positional and inflexible. Moreover, you don’t want to stop the clients from considering and, if acceptable, agreeing to things that may be contrary to their rights and responsibilities “under the law.”

Explaining the law is not to dissuade clients from agreeing on things. Rule 3.2.A. of the Standards and Ethics provides for a Collaborative Professional to respect each client’s self-determination, recognizing that ultimately the clients are responsible for making decisions that resolve their issues. Similarly, Rule 4-1.2 RRTFB, Objectives and Scope of Representation, provides for lawyers to respect client decisions: “A lawyer must abide by a client’s decision whether to settle a matter.”

“Informed consent” is the operative phrase in all aspects of the clients selecting the Collaborative Process, during the Process itself, and reaching a resolution.

We have described ethical rules enforceable against the attorney’s license and collaborative ethical rules, not enforceable against the attorney’s license. Professional ethics and Collaborative ethics overlap. But there are differences. Could the Collaborative Law Process work with only having the professional ethical rules and no Collaborative Standards and Ethics? I would suggest not. Do the Collaborative Ethics negate the professional ethics? Certainly not. They enhance them if anything.

But the IACP Standards and Ethics are needed for there to be a strong Collaborative Law Process and for it to succeed. The Standards and Ethics help implement the legal requirements of the Collaborative Process. The Standards and Ethics make the Process what it is and define its differences from other forms of dispute resolution.

The Collaborative Law Process is a voluntary, open, and transparent process and the Standards and Ethics make certain the process stays that way throughout the entire process. Only by Collaborative Professionals observing these Standards and Ethics can the Collaborative Process succeed.

The Standards and Ethics may not be enforceable, but they are far from aspirational. They are foundational and structural, like beams and girders. They give the Collaborative Process integrity. Solid ethical standards may be the cornerstone around which the Collaborative Professionals and their clients construct the Collaborative Law Process. For the Process to stand strong, the Collaborative Team, including the clients, must follow them.